Dear Reader, Panda Perspectives is a finance-first publication. Our focus has been and will be squarely on China and Chinese Equities. Nevertheless occasionally I feel strongly about some geopolitical developments, and I feel the need to weigh in, at the very least with a view on some threads that are maybe being ignored in present day coverage. So if you are new to us, please take the opportunity to sign up!

So yes, I am talking about how the events in Syria will impact China and its markets. Why is a finance publication delving into this topic? Is it Mr. Panda reminiscing about his childhood in the Soviet Union?

A) Please, call me Leonid.

B) No—there are tangible implications for risk assessments, market perceptions, and equity valuations stemming from these geopolitical shifts.

I believe that the Syrian Regime’s downfall is both the symptom and the likely the blueprint for the Traditional Dictator Class. There aren’t that many left but there are some. Most of them are in the general are once occupied by USSR.

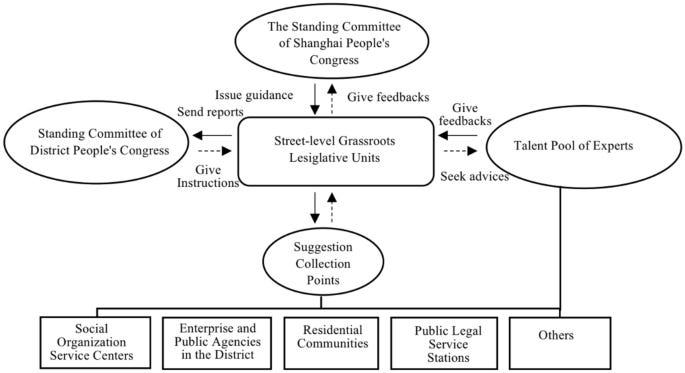

I want to make a very clear distinction: China’s concept of “whole-process democracy” presents itself as fundamentally different from the regimes of Bashar al-Assad in Syria or Vladimir Putin in Russia, even though it operates outside the framework of Western liberal democracy. While all three governments reject the Western model of electoral democracy, the similarities largely end there. China’s model is built on a structured, systematized approach designed to reflect popular will while emphasizing governance efficiency and long-term stability. In contrast, the Assad and Putin regimes are often characterized by personalist rule, suppression of dissent, and a prioritization of regime survival over systemic reform.

Assad may not be comparable to others in his position, given his propensity to wage war on his own people for such a prolonged period of time, but that distinction makes his case even more applicable to understanding the shifting global order. Was he truly shot down in that plane, or was this a strategic decoy? Does it even matter? What we are witnessing across Syria is symbolic of a larger transformation: the figurative and literal dismantling of monuments to all the Assads—a broader reckoning with entrenched regimes and outdated paradigms.

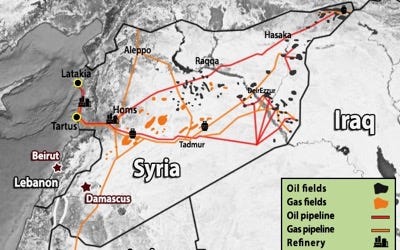

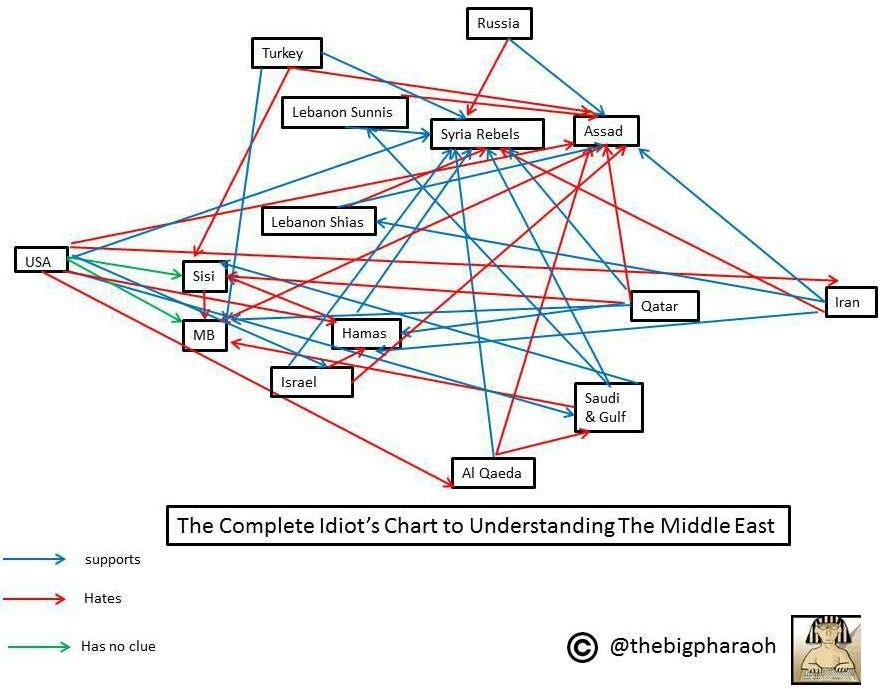

Syria represents more than just a singular conflict; it embodies the last bastion of a bygone era, the remnants of a Soviet-influenced geopolitical framework. As the Soviet Union’s legacy fades, so too does the influence of its relationships, leaving nations like Syria to navigate a redrawn map without the safety net of Cold War-era alliances. This is not to say these ties have vanished completely—they persist in fragments, echoing in strategy and ideology—but their relevance is waning. The maps are indeed being redrawn, marking the end of the “old” order and the emergence of something new.

The toll of physical warfare is another stark reminder of the constraints imposed by the real world. Russia, for instance, finds itself stretched too thin to effectively wage battles on three fronts simultaneously. While its aspirations may extend beyond its reach, the physical realities of war—logistics, resources, and geography—impose inescapable limits on any actor, no matter their ambitions. This serves as a cautionary tale for budding geopolitical analysts: decisions do not exist in a vacuum. The cascading third- and fourth-level effects of an initial action often reveal themselves as critical constraints only downstream, reshaping outcomes in ways that are not immediately obvious.

Sanctions, though often slow-acting, have proven to be a formidable tool in exerting economic pressure, effectively leading to a “death by a thousand cuts” for targeted nations. Russia’s current challenges in maritime operations and aviation maintenance exemplify the cumulative impact of these measures.

The United Kingdom has intensified its sanctions against Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet”—a group of vessels operating clandestinely to transport Russian oil in defiance of international restrictions. Recently, the UK sanctioned 30 ships involved in these illicit activities, aiming to disrupt a significant revenue stream for Moscow’s war efforts in Ukraine. This action brings the total number of Russian tankers sanctioned by the UK to 73, the highest by any nation.

In the aviation sector, Western sanctions have severely restricted Russia’s access to essential aircraft components. Aeroflot, Russia’s flagship carrier, has resorted to purchasing used Boeing aircraft from lessors to maintain its fleet, as acquiring new planes or parts otherwise has become increasingly difficult. Additionally, Russian airlines have grounded 34 of their 66 Airbus A320neo family aircraft due to unresolved engine issues, a situation exacerbated by the inability to procure necessary parts from Western manufacturers.

These developments underscore the efficacy of sustained sanctions in imposing economic constraints. While the effects may not be immediate, the gradual accumulation of restrictions hampers a nation’s operational capabilities across critical sectors, leading to significant long-term challenges. Most of the impact if of course felt domestically, as Russians have to deal with a limited choice of higher priced goods (admittedly the limits aren’t what the west was hoping for but still), greater risk when flying domestic airlines and greater Rouble volatility and ultimately weakness.

In this broader context, Syria is not just a case study in modern conflict but also a lens through which we can observe the death of mercantilism, the reconfiguration of power dynamics, and the eventual prioritization of domestic stability over external ambitions. It is a stark reminder that, in the modern era, no actor is immune to the immutable constraints of the physical world and the shifting tides of the global order.

Mercantilism is an economic policy framework that dominated Europe from the 16th to 18th centuries, built on the belief that a nation’s wealth and power were best served by maximizing exports and minimizing imports. The goal was to accumulate gold and silver reserves and achieve a favorable balance of trade through state intervention, tariffs, and trade protectionism. While the gold-accumulation focus of classical mercantilism has disappeared, its principles still manifest in certain export-driven economies today, such as Germany and Japan.

Russia exemplifies a modern mercantilist and expansionist state, relying heavily on raw material exports—particularly oil and gas—to fund its geopolitical ambitions and sustain its war efforts. Energy exports account for over 40% of its federal budget revenues, making external trade central to its economy. To maintain competitiveness, Russia deliberately weakens the ruble, ensuring its exports remain attractively priced. However, this comes at the cost of eroding domestic purchasing power and suppressing internal demand, hallmarks of mercantilist thinking.

Russia’s strategy extends beyond economics to geopolitics, using its energy exports as leverage, such as cutting off gas supplies to pressure opposing nations. This approach funds military aggression, like the war in Ukraine, while supporting its broader expansionist goals. However, over-reliance on resource exports leaves Russia vulnerable to sanctions, fluctuating commodity prices, and the global shift toward renewable energy. This mercantilist model, focused on external revenues over domestic resilience, risks making Russia’s economy brittle and its expansionist ambitions increasingly unsustainable.

Germany and Japan remain modern examples of mercantilism due to their overwhelming reliance on exports to fuel economic growth. Germany, often called Europe’s “export powerhouse,” derives a significant portion of its GDP from exports, particularly in high-value-added industries like automobiles, machinery, and chemicals. As of 2023, exports accounted for approximately 45% of Germany’s GDP, one of the highest ratios among developed economies. Similarly, Japan heavily relies on global demand for its automobiles, electronics, and industrial machinery. While Japan faces domestic challenges, such as an aging population and sluggish internal demand, it remains a significant player in global trade, consistently prioritizing export-led growth.

Both nations have historically pursued trade surpluses, a hallmark of mercantilist policies. Germany’s trade surplus in 2022 stood at €80 billion despite global economic disruptions, while Japan has posted significant trade surpluses throughout much of the 20th century, becoming synonymous with high-quality manufacturing and competitive exports. Another defining feature of mercantilism is the suppression of domestic consumption to ensure production exceeds local demand, leaving room for exports. Germany and Japan both exhibit relatively low levels of household consumption as a share of GDP compared to other advanced economies. In 2023, household consumption accounted for only about 50% of GDP in Germany and 55% in Japan, compared to nearly 70% in the United States. This reflects a structural reliance on external demand rather than internal consumption to drive economic growth.

State support for key industries further exemplifies their mercantilist tendencies. In Germany, industrial policies and vocational training systems bolster its manufacturing base, while Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) guides industrial strategy, supporting sectors like robotics and technology. While neither country perfectly aligns with historical mercantilism, their economic strategies prioritize exports, trade surpluses, and state-supported industries, hallmarks of the mercantilist mindset. However, this orientation leaves them vulnerable to global economic shocks, shifting consumption patterns, and protectionist policies abroad, highlighting the need for a more balanced approach in the future.

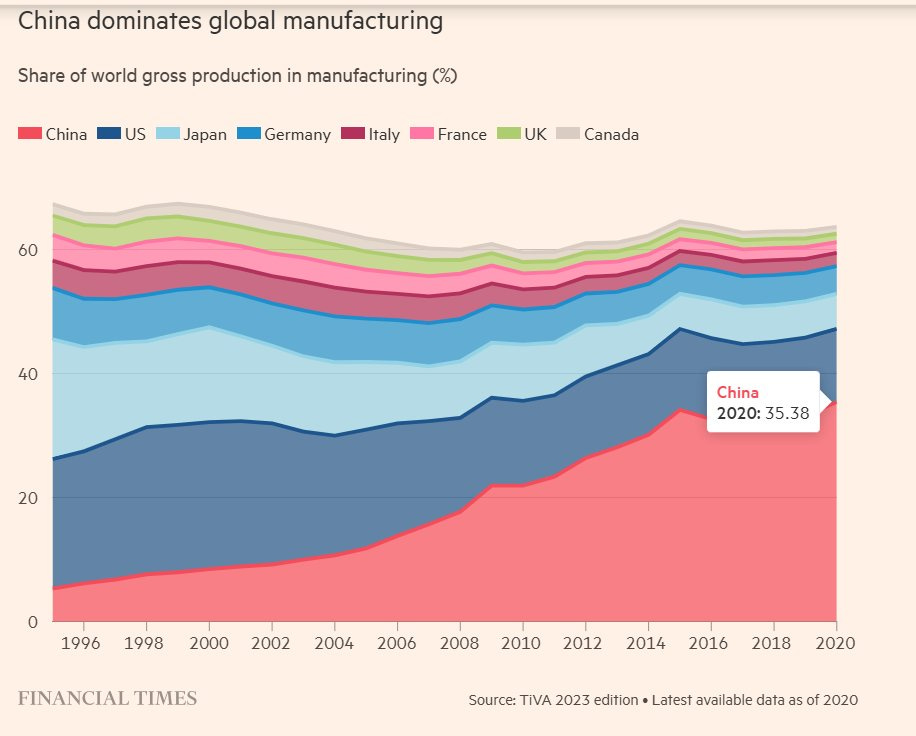

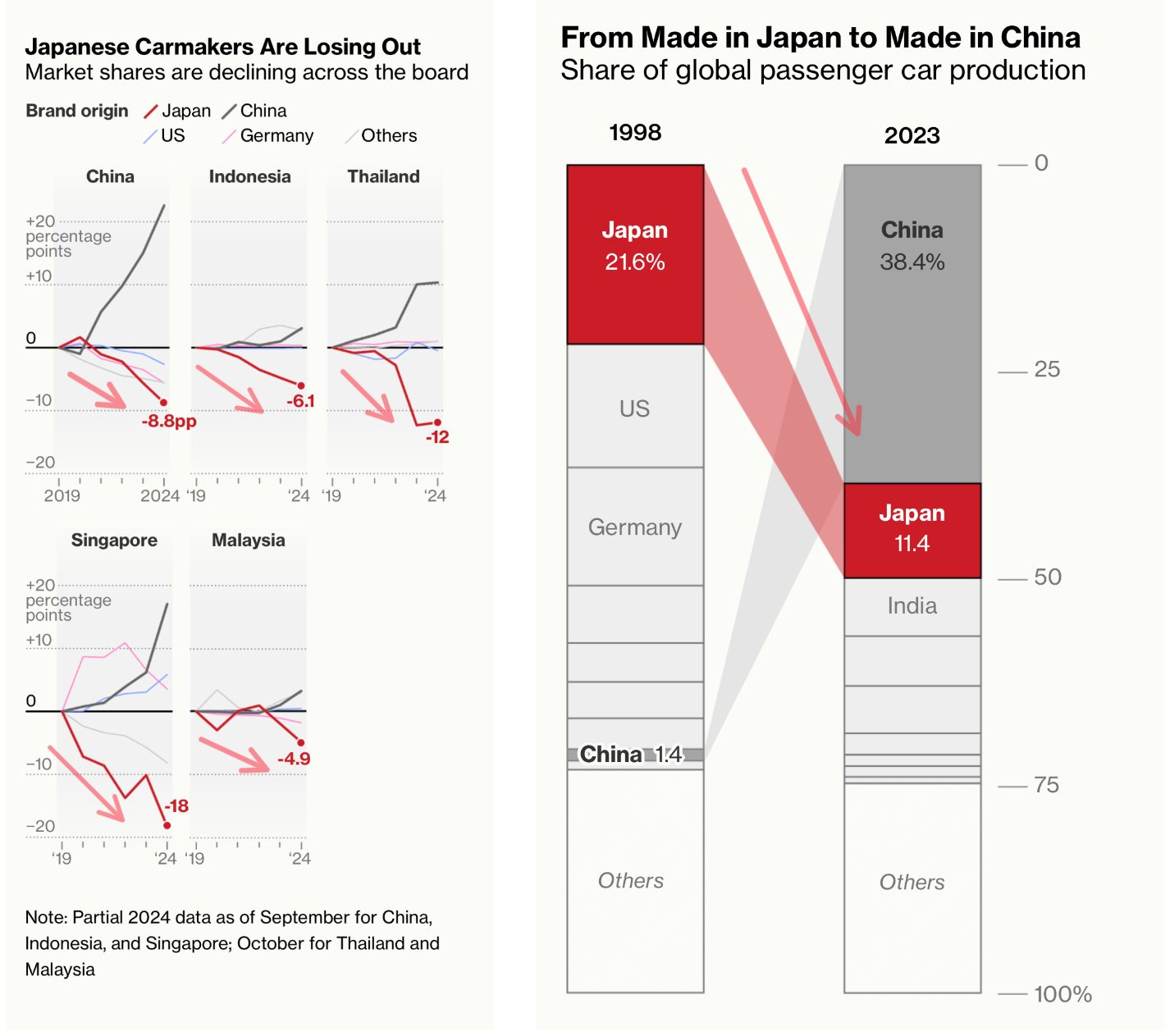

The decline of mercantilism is starkly reflected in the challenges faced by export-reliant economies like Germany, Japan, and Korea. These nations, once economic powerhouses, have seen their combined share of global GDP steadily decline, dropping from nearly 20% in the early 2000s to approximately 15% today. This shift underscores how heavy dependence on external demand leaves these economies vulnerable in a world where global consumption patterns are increasingly fragmented. The trade disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with shifting supply chains and regionalization, further highlight the pressing need for these nations to foster robust domestic demand as a more sustainable growth strategy.

Mercantilist-oriented models, like those seen in Germany and Japan, face a fundamental issue in their underlying philosophy: the perception of exports as inherently “good” and imports as inherently “bad” because they view trade as a zero-sum game where foreign currency either fills or drains national coffers. This approach misses the central point of capitalism: reciprocal trade, not hoarding surpluses, is what drives long-term economic growth. True reciprocal trade thrives on strong domestic demand, which allows for a healthy exchange of goods and services across borders. By focusing excessively on exporting while suppressing imports and domestic consumption, these economies risk undermining their own resilience. Should export markets be disrupted—whether by global economic shocks, geopolitical tensions, or protectionist measures—these economies suddenly face the problem of overproduction. With insufficient domestic demand to absorb the surplus, their economies become brittle, exposing a structural vulnerability that leaves them ill-prepared for changing global dynamics.

China provides a compelling case study in this context. Historically, its economic model relied heavily on export-oriented growth, as exemplified by its dominance in industries like electronics, textiles, and machinery. Even during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), China’s exports of silk, tea, and porcelain were key drivers of its economic strength. However, the tides are shifting. Today, domestic consumption accounts for more than 60% of China’s GDP, indicating a gradual but vital rebalancing effort toward a more sustainable growth model.

Interestingly, not all export-driven trade aligns with the outdated mercantilist mindset. In many cases, foreign demand for high-quality or innovative products serves as a natural economic driver. For instance, China’s leadership in exporting high-tech products like electric vehicles, solar panels, and smartphones reflects global demand for quality and technological advancement. In 2023 alone, China’s EV exports surged by 93%, fueled by growing international recognition of brands like BYD and Li Auto.

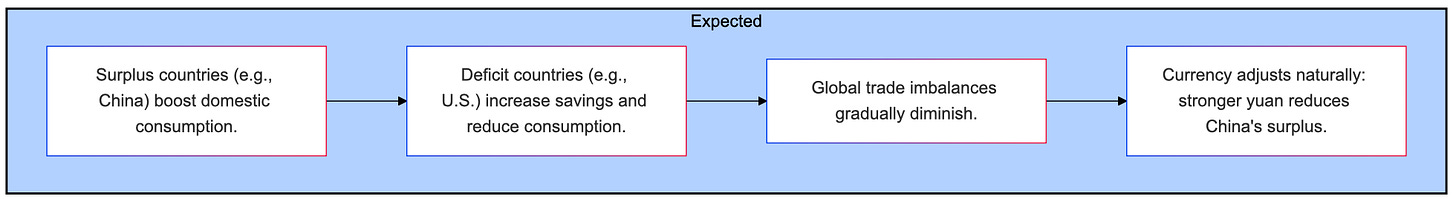

In an ideal global framework, surplus economies like China would shift their focus toward boosting domestic consumption, while deficit nations such as the United States would increase savings and reduce excess consumption. Such adjustments are critical to alleviating trade imbalances and fostering long-term economic stability. For example, China’s efforts in recent years to stimulate domestic consumption—through measures like tax cuts and consumer subsidies—have begun to yield results, with retail sales growing by 8% annually in the years leading up to the pandemic.

In reality, however, the current dynamics tell a different story. China continues to maintain export-driven growth underpinned by high savings, while the United States sustains its consumption habits, financed by substantial external capital inflows. This dynamic perpetuates trade imbalances, fostering economic instability. For instance, China’s trade surplus with the U.S. reached a staggering $323 billion in 2018, exacerbating trade tensions that led to a series of tariffs and counter-tariffs between the two nations. These imbalances highlight the risks inherent in such economic models, as sustained asymmetries can destabilise global markets.

For China, prioritizing domestic demand has become essential for ensuring economic resilience and state security. The U.S. has similarly discovered that its robust domestic consumption remains a cornerstone of the dollar’s strength, outpacing even its military influence. This shift toward domestic demand and innovation as drivers of economic power may well define the modern era of global competition.

China has already made significant strides in shifting its economic focus toward boosting domestic demand as a cornerstone of its long-term growth strategy. Recognizing the vulnerabilities of an export-reliant model, the Chinese government has implemented policies to stimulate household consumption and diversify growth drivers. Initiatives such as tax cuts, subsidies for key consumer sectors, and investments in social welfare programs aim to increase disposable income and reduce savings rates. The government’s “dual circulation” strategy explicitly prioritizes domestic consumption while maintaining competitive exports. Early results are evident in sectors like retail, where domestic sales of goods and services have steadily grown, contributing over 60% to GDP growth in recent years. By fostering a robust consumer market, China is positioning itself for greater economic resilience and reducing its reliance on volatile global trade dynamics.

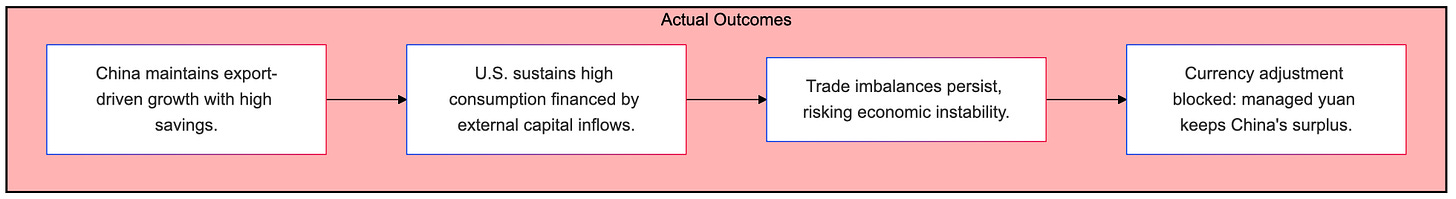

It is also intensifying its ties with The Belt and road nations, which is a clear shift China’s trade strategy, moving away from reliance on the United States and toward stronger engagement with non-Western regions. From 2018 to 2024, the U.S. share of China’s total trade dropped significantly, declining by 2.9 percentage points, from 13.7% to 10.8%. In contrast, China’s trade with ASEAN nations increased sharply, rising by 3.2 percentage points to 15.9%, making it the largest regional trading partner. Similar upward trends are evident with Africa, Russia, and Latin America, reflecting China’s effort to diversify trade relationships and reduce dependency on Western markets. We will address the technical aspects of this pivot, including the proposed new currency regime in a separate post.

Nevertheless the final solution to this vulnerability is robust domestic demand. We have discussed at length in previous articles that I bodes well for RMB-denominated assets and Chinese assets in General.

The death of mercantilism signifies not only a shift in economic priorities but also a reimagining of geopolitical strategies. Nations must adapt to these changing dynamics by fostering self-reliance and internal growth. For investors and policymakers alike, this transformation brings profound implications for risk assessment, market perceptions, and equity valuations. As monuments to the old order crumble, the future will belong to those who embrace this new reality and invest in domestic demand as the cornerstone of economic strength.