There will be a new press conference on Thursday morning covering the housing market. This column has already *almost* awarded victory over the housing market to the yet unconfirmed and thus unspent stimulus package, but we concede that we do at least need to see the implementation plans, so we anticipate being here tomorrow to dissect that. But this being on Thursday also means that there’s time to explore a more theoretical idea, namely with all this stimulus talk – what are the limits to it? At what point does the Chinese government run out of fiscal runway?

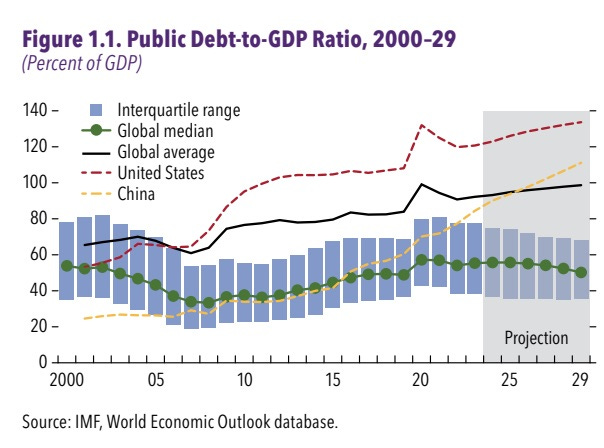

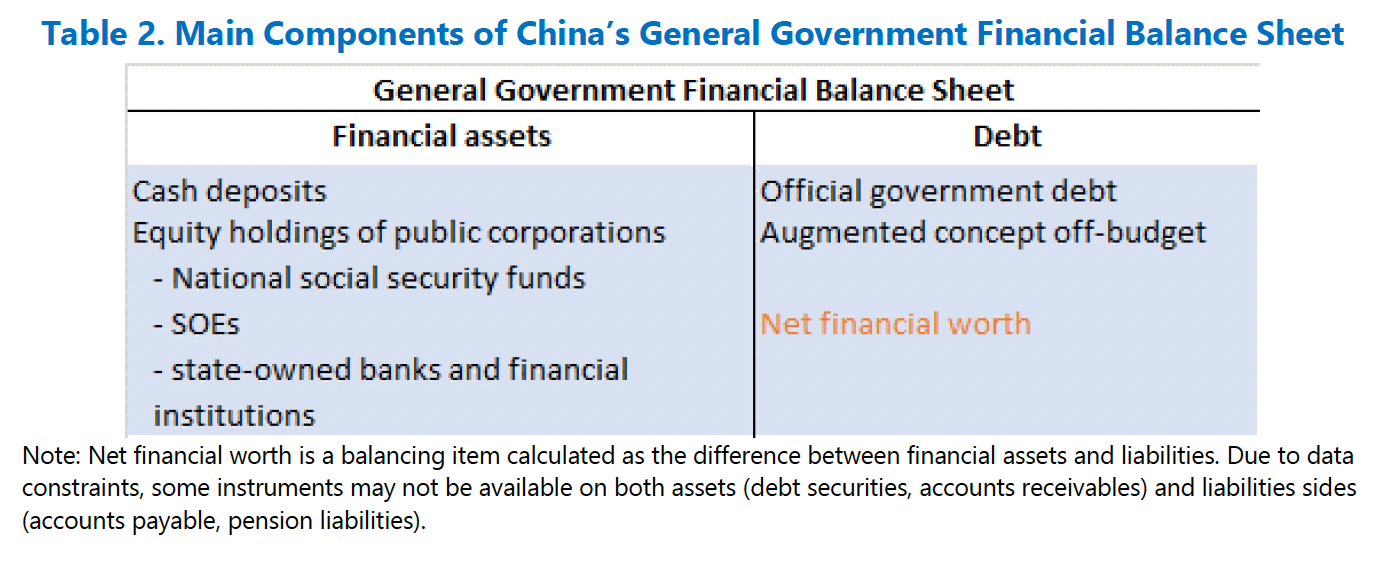

This char form the IMF was floating about the social media econosphere and it has not escaped our attention, so much so we had to do a double take. Look at this yellow line! Just look at it! So steep, so problematic! Ad yet it is the belief of this here newsletter that its got plenty of room despite what you hear about the level of indebtedness. This is because one ought to consider the entire net worth of the government and the Chinese government is in an excellent position. Consider what goes in to that fiscal balance sheet. Both figures are from IMF, even if some data is a little dated now.

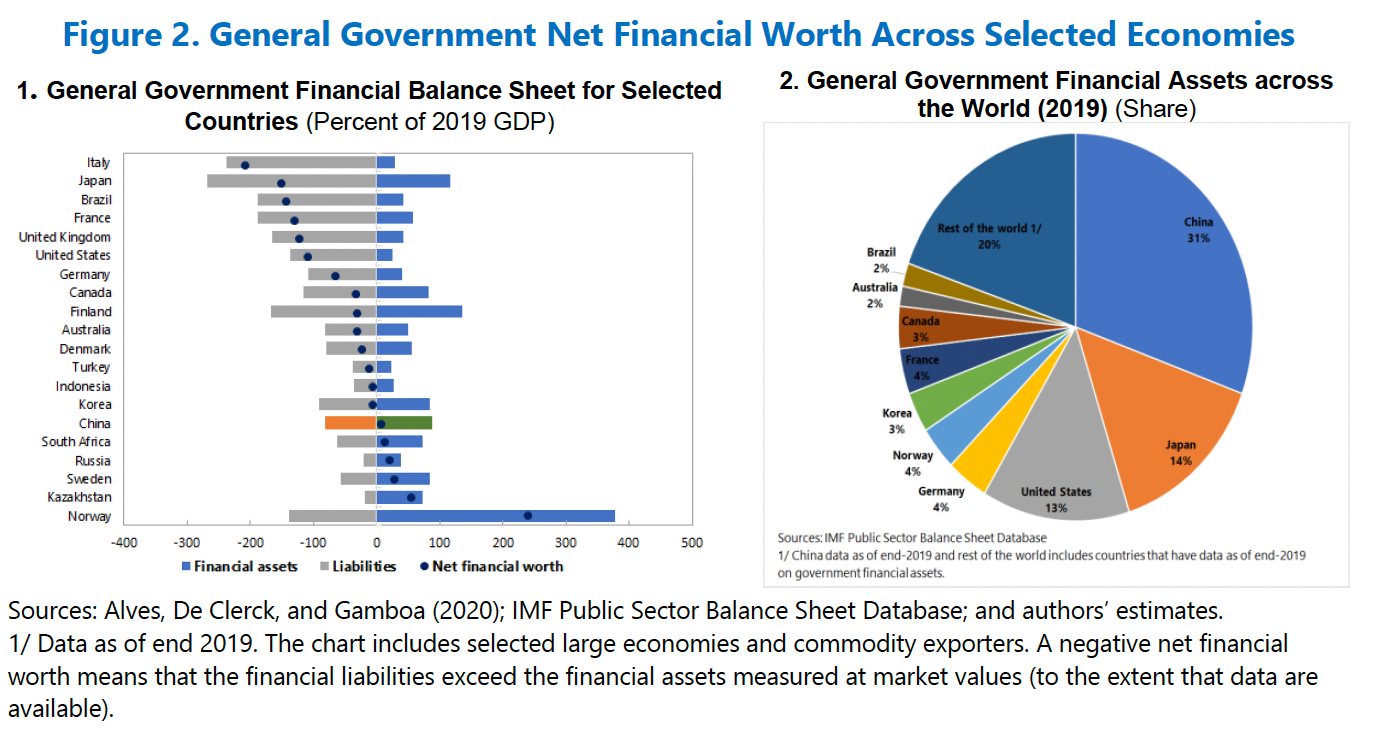

China’s fiscal muscle is more than just flex-worthy. With direct central government debt sitting comfortably under 30% of GDP and funding costs at a mere 2%, Beijing has the luxury of favorable debt dynamics. Toss in China’s robust asset portfolio—packed with external assets that outstrip liabilities and equity stakes in state-owned enterprises—and the fiscal cupboard is far from bare. On that net basis shina looks good, and it is also a very large financial asset owner in its own right. Not to say that selling those down for stimulus is the move, rath that borrowing is much more secure than it appears at first.

But wait, there’s more. Even if you factor in the dreaded contingent liabilities, China’s net debt still lounges around a modest 25% of GDP. Sure, the general government’s debt hovers at 63% of GDP, but with low interest rates on the side, it’s manageable. And as for that oft-cited augmented fiscal balance? It’s more like an outdated relic from the post-financial crisis era—hardly the right lens for today’s fiscal reality.

Similarly the Local Government’s balance sheet is in a better state than the sheer debt numbers have you believe, but we will leave that to one side for the time being. Just to note that in both cases a general asset price appreciation across the Chinese economy improves the net fiscal position, which has not escaped policymakers we believe.

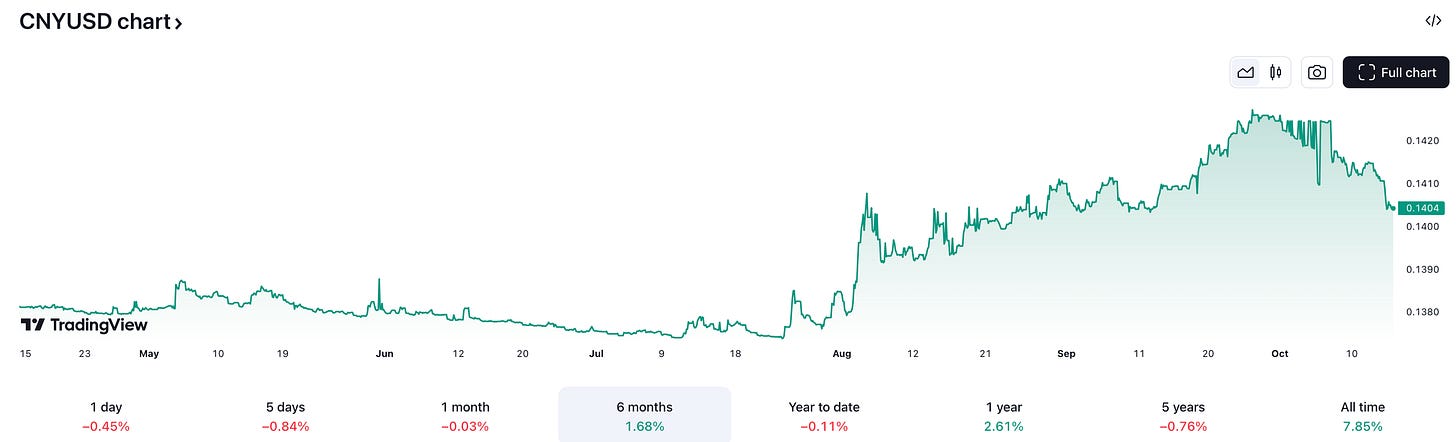

But surely there’s nevertheless a limit? So at what point do we know that the stimulus has gone too far? IT is not the question that’s at the forefront of everyone’s mind, as the current issues seem to be focused on getting enough stimulus out there. But given the excess saving and the dearth of activity, a coiled spring scenario is not out of the question. So what will be the indicator? This should be fairly straightforward: it’s the currency. It will go first and will be a canary in the coalmine.

One ought to pay close attention to the offshore CNHUSD rates as well as the CNYUSD for the slightly different takes on what Is the most balanced view on the markets view on the success of the stimulus program, but there’s an issue. Currency markets are volatile so how does one determine that the canary that’s now dead is the canary from our mine?

To wit, today the RMB (or CNY) fell to a one-month low against the dollar, breaching the 7.1 per dollar level due to seemingly weak domestic economic data and expectations of steady U.S. interest rates. So it appears that despite efforts by Chinese authorities to boost growth, disappointing export figures add to the economic challenges. However the question then arises doesn’t this increase the likelihood of further government reaction?

The yuan’s recent weakness can be traced back to a few key factors. First, lower Chinese interest rates, combined with a widening interest rate differential between China and the U.S., have made the yuan less attractive to investors. PBOC has come out very doveish in September and arguably got the stimulus rain going, while the U.S. Federal Reserve has been raising rates in response to persistent inflation. Similarly, rising expectations of even fewer U.S. cuts, driven by inflation, are adding further downward pressure on the yuan.

Looking at the charts, a story emerges. The yuan has moved first, in August, well in advance of the stimulus announcements, but following the US move to star cutting rates. And this move happened against the stock market. Then in September the stimulus story hit and the currency and the markets have started moving together, in anticipation of a plan that resolves Chinese economic concerns. Certainly thre’ s more volatility in the equity, which makes sense, but the two clearly moved together, up at first but down more recently.

Clearly the concern the market has, as discussed above, whether the announced policy is enough. The point we keep coming back to is that a very important part of this push is to get the locals to invest (as discussed yesterday). But second after that is the desire to return the exporters cash.

Consider the following, Chinese exporters, when expecting yuan weakness, have been strategically holding onto their export revenues in foreign currencies. By delaying the conversion of their earnings into yuan, these exporters are picking optimal times to meet their domestic obligations, exacerbating short-term yuan liquidity issues and weakening the currency even more. For a moment the opportunity cost of having the cash overseas got too high, but now the effect may be wearing off.

Understanding these moving parts indicate that to consider the stimulative police changes successful we need to see it being confirmed in higher CNY. Given the pressures of interest rate differentials, we are not expecting a test of 6.50 or anything like that in the very near future, but a firm move above 7 will be that signal. From that point on we monitor for signs of significant RMB weakness, especially weakness that is strong enough to suggest trend reversal. That may start showing that the stimulus perhaps over did it.

WE do note however that In the world of currency pairs, it’s never just about one country’s policies. Exchange rates are a tug-of-war between two sets of economic forces, and in the case of the yuan-dollar pair, China’s moves can’t be seen in isolation. U.S. policies—like the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes or inflation control measures—directly impact the dollar’s strength, which in turn influences the yuan’s value. And it just so happens that the US is also having to make a big decision on its future in just over 30 days from now (At the time of writing). It appears this collum may need to pinch its not and dive in head first in to the pool of political discourse around the US election and contribute to the healthy debate on the subject of Trump and Harris implications, or on the implications for China, Asia and world Trade at the very least.