In Chinese vernacular, “the British Disease” is typically referred to as “英国病” (Yīngguó bìng). This term historically refers to economic issues that plagued the UK, such as stagnation, high inflation, and labour strikes, often attributed to inefficiencies and structural issues in industry and government. In the Chinese context, it is sometimes used as a cautionary term when discussing economic challenges related to industrial decline or excessive reliance on government intervention. That is to say in China its widely accepted that the UK was the architect of its own demise (as a global power) and the chief among policy failures was government intervention and the safety net that’s too high. A surprising development for anyone who keeps calling China Marxist, but there you have it. Moral hazard by any other (Chinese) name, if you will. What follows is an exploration of how China is thinking about direct stimulus.

But first, some housekeeping, paid subscribers can expect 2 more notes this week, as we continue the exploration of the EV space. We have X-Peng (XPEV US) and Zeeker (ZK US). The week after we are entering the realm of data crunching where instead of focusing on individual companies, I will present my broad sectoral views and do some relative valuation work. As usual I invite everyone to join the paid ranks as that’s where we can deal with your questions and discuss the EV and indeed any other sector you may be wondering about including discussing this note. And given it’s 11.11 today (for most of us) - there’s a special offer on to get 25% off forever if you subscribe today!

But enough of that – on to the main discussion.

I bring up the “British Disease” here to provide context for the pacing of China’s stimulus expansion and to illustrate why the seemingly simple solution of direct cash distribution to boost spending remains challenging for the Chinese government. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) recently wrapped up a week-long session, approving a substantial 12 trillion RMB stimulus package led by the Ministry of Finance to address local government debt. This package includes a 6 trillion RMB debt swap over three years, an additional 4 trillion RMB in special-purpose bonds, and 2 trillion RMB for shantytown renovation.

Yet, despite the impressive scale of these measures, markets remain skeptical due to the absence of direct consumption-driven stimulus. As discussed with

recently on The Market Huddle, understanding that policy adjustments will continue until they meet the necessary impact is challenging. The market is currently laser-focused on direct stimulus, despite substantial steps made in other areas. The reluctance to deliver immediate consumption support underscores the Chinese government’s cautious approach, favouring deliberation and a full NPC session’s approval before making moves that could reshape household spending power directly.Consider the Ministry of Finance’s new debt plan, which raises the local government debt ceiling to 35.52 trillion yuan, sets a three-year target to increase debt by 6 trn RMB (2 trn annually from 2024 to 2026). This debt capacity is intended to replace existing hidden debt (隐性债务), freeing local governments to prioritize economic support over debt servicing. Additionally, China will allocate 800 bn RMB annually through special bonds, totalling 4 trn RMB over five years, to reduce hidden liabilities burdening provincial budgets. This arrangement is projected to save approximately 600 bn RMB in interest. The stimulus also covers 2 trn RMB for shantytown renovation (棚户区改造), due in 2029 and beyond, which will adhere to original contracts.

Yet, the package has underwhelmed the market, primarily due to its indirect approach, focusing on fiscal support rather than direct consumption stimulus, sending Chinese names in the US down 5-10% on Friday as scepticism over the government’s reluctance to stimulate direct spending persists. I on the other hand am confident this will get done, eventually, but why is it taking so long to approve?

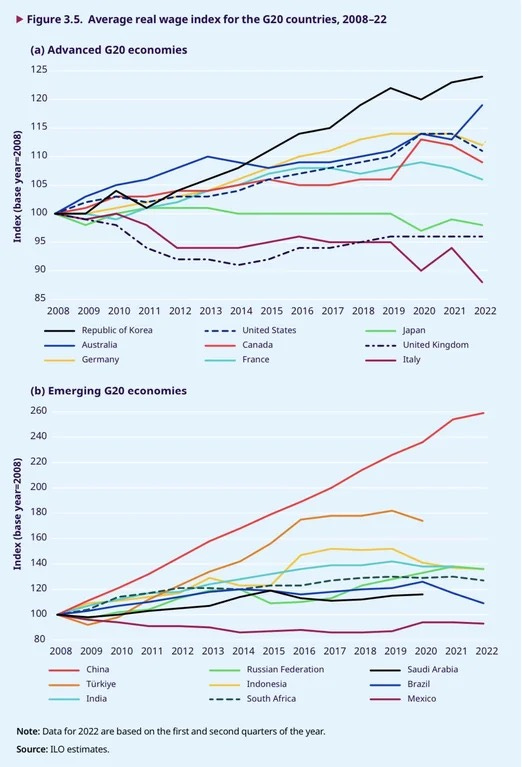

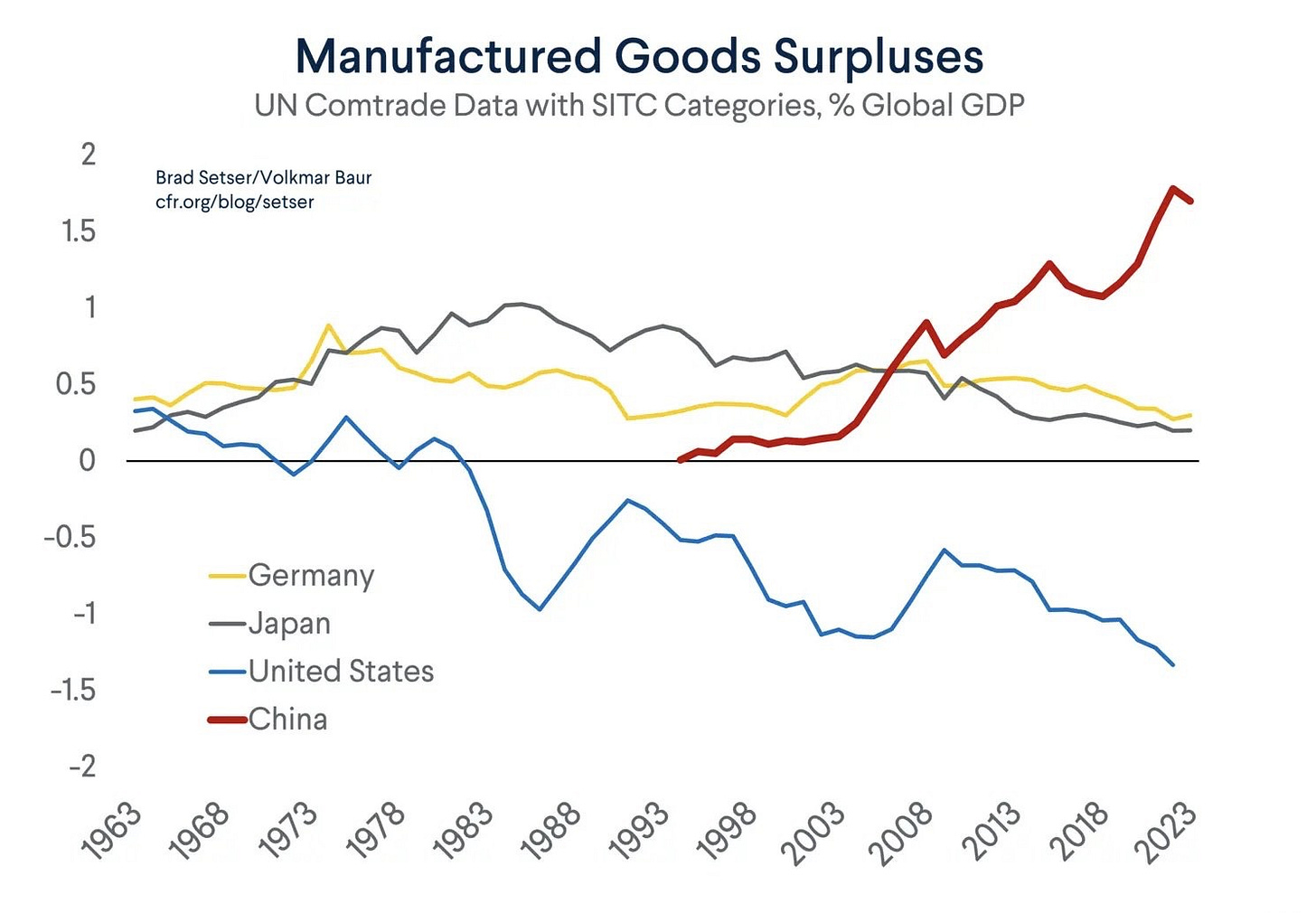

One ought to think back to the late 1970’ and early 1980s. Deng’s success internally was based on a) not being Hua Guofneg but b) an ability to distil the economic success of Asian tiger economies to being an export model, and then to implement it and deonstarte immediate results. The export focus proved to be very successful for every Chinese leader or Cadre who bet on it. So much so that arguably China took it to the very limit of what is feasible using this model. When Japan, Korea and Hong Kong, while large economies, never threatened to make manufacturing elsewhere unviable. China’s success made sure that it remains the manufacturing centre despite being able to grow worker salaries much faster than other markets.

There is more to the story to exports than just efficiency, and I fully acknowledge that the policy choices in US and in China made it difficult to adjust. If it weren’t the case, Chinese manufacturers with significant profits would see similar growth accrue to its workers in the from higher wages, and the result should be higher consumption, which in turn should be balanced by higher imports. But that clearly isn't happening. Similarly, the US should have experienced a weaker dollar in response to continuous trade deficit, but again instead we’re seeing ever increasing capital account surplus and debt issuance. US has been all too happy to continuedly absorb other countries surpluses (manufacturing and otherwise). This is a complicated topic and I don’t want to go in to too much detail on this, but for our purposes I am pointing out that we may have hit limits to the export growth model well in advance of the CPC leadership falling out of love with it. It wont hurt that this time Trump administration may offer a push from the US side too.

I would summarise the situation as follows: Chinese leadership recognises the virtues of a balanced budget, low debt and manufacturing as a driver. I t undervalues domestic demand, fearing the British Disease first and foremost. Immediately it should be obvious that this is much closer to German-style mercantilism than a socialist or a US-style market economy, Thus China’s strategy exemplifies a controlled approach to fiscal prudence and expectation management. Increasing the debt limit aims to lower debt servicing costs by replacing high-interest hidden debt with lower-interest options, which could save an estimated 400 billion yuan. Even verbally, Finance Minister Lan Fuan has stressed the importance of maintaining a strong fiscal policy while managing inflationary risks.

The Change is coming, however. The urgency for China to boost domestic demand is even more apparent amid shifting global trade tensions, especially with the potential of increased tariffs from the U.S. If China strengthens its domestic demand, it could drive global inflation higher, potentially limiting the U.S.’s ability to impose substantial tariffs. Conversely, weaker Chinese demand could reduce inflationary pressures, giving the U.S. more flexibility to impose tariffs. This interdependence underscores the urgency of China’s strategic domestic demand expansion as both a defensive and economic necessity.

Even in relations with EU, that China saw as being in a better place than the US, China has been getting significant pushback. Look no further than the EV tariffs – clearly a sign that EU is concerned about the total amount of imports from China and giving Chinese companies access to its domestic market thereby helping to foster competition for EU manufacturers globally. Now clearly EU manufacturing is declining due to energy policies and impacts of the war in Ukraine, nevertheless its example of maximizing market access as a leverage point. This serves as a reminder that demand is an assets and freezing Chinese manufacturing capacity form its 2 key markets has reminded the CPC core of the changing nature of the world.

I am confident that there is a change in the air. In 2024, senior Chinese officials have repeatedly stressed the critical role of domestic demand in driving economic growth. Starting from December 2023, the Politburo highlighted plans to prioritize spurring domestic consumption to strengthen and sustain economic recovery efforts. By mid-2024, NDRC’s Yuan Da underscored that promoting domestic demand was now central to economic policy, aiming to enhance consumer spending. In line with this, Chinese leadership has also pledged to raise household incomes, especially among low- and middle-income groups, to support a shift towards a consumption-driven economy and reduce dependence on exports and investment-led growth. All of it is exactly in line with what I think they should be doing.

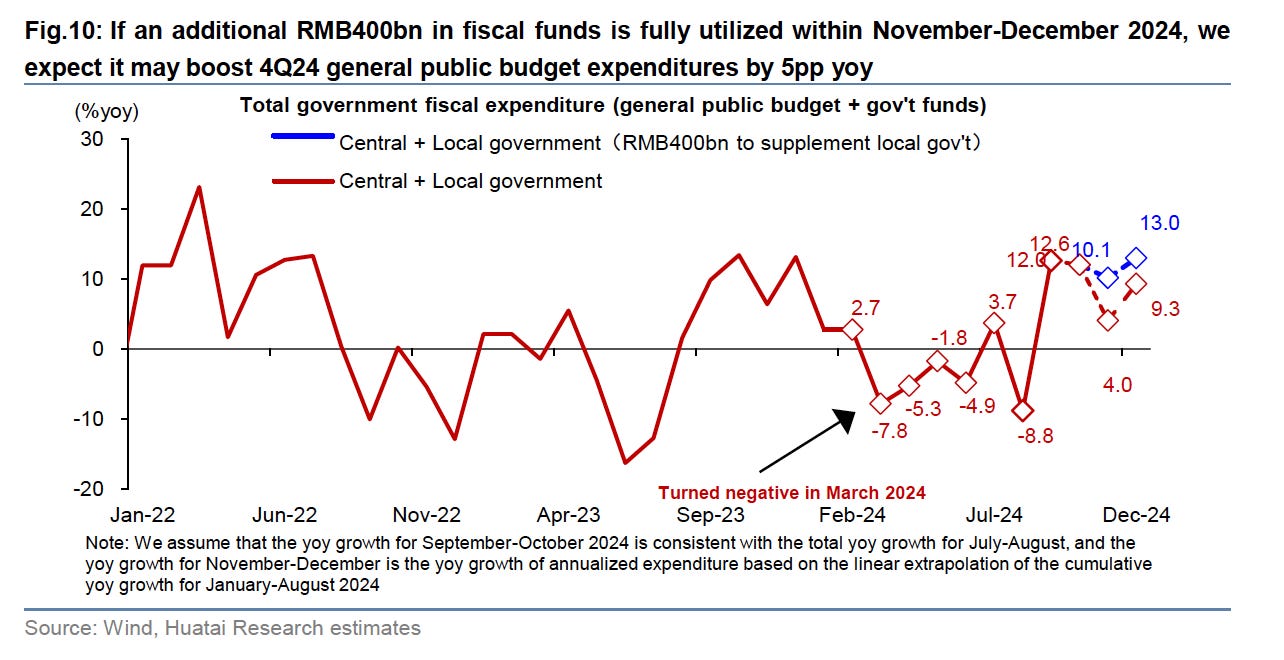

Recall, On October 12, the Ministry of Finance announced two key initiatives: 1) a commitment to meet the full-year budget targets, primarily concerning the general public budget. We estimate this could result in a 9.2% year-over-year growth in general public budget expenditures for Q4 2024; and 2) the central government will allocate RMB 400 billion (annualized to over RMB 2 trillion) to support local governments. Alongside this, NDRC will provide an additional RMB 200 billion in funding for local investment projects. Together, these measures are expected to drive year-over-year fiscal expenditure growth for Q4 2024 by over 5 percentage points, supporting China’s efforts to meet its 5% economic growth target for the year. This is to say that the policies that have been announced in September and October will be having an impact, and as they do it reduces the urgency of the need for direct stimulus (char below courtesy of Huatai Research).

This makes sense as one breaks down some of the policies that have been passed, they are clearly designed to trickle down to consumption eventually. Special bonds will support large-scale projects without directly impacting household incomes, thus controlling inflation. Lan Fuan’s focus on technological upgrades underscores China’s commitment to long-term economic resilience rather than short-term boosts, but boost to consumption nevertheless. These bonds also assist in reclaiming idle land and converting commercial properties into affordable housing, providing relief for the struggling real estate sector and nother form of transfers to the low-income households. Additionally, central transfer payments will fund critical areas such as technology and social welfare, indirectly promoting sustainable growth.

Upcoming measures include issuing special sovereign bonds to strengthen major state banks, new policies to support the real estate market, and special bonds for acquiring idle land and unsold properties. By 2025, China plans a more assertive fiscal strategy, with expanded local government debt issuance and ultra-long-term treasury bonds to provide additional economic support.

But even this stimulus package is both a display of strength and caution. China’s plan to roll out additional debt relief measures and policy adjustments shows a commitment to a gradual, calculated economic adjustment. Planned measures include issuing special sovereign bonds to support state banks, new real estate support policies, and special bonds for land acquisition. By 2025, China plans a more assertive fiscal approach, including expanded local government debt issuance and ultra-long-term treasury bonds to drive sustained economic momentum.

P.S. Another point to note is how involved NDRC is getting in feedback and data from private enterprises. They call it fostering collaboration with private enterprises, but to me its clear they have understood that private enterprises have a much better handle on the domestic dynamics, and on export market accesability. Hence the implemented regular communication strategy with private sector leaders. Each date in a series of high-level meetings throughout 2024 marks key moments in developing structured dialogue between the NDRC and private businesses, particularly export-oriented and innovation-driven companies. Notably:

• October 25: A meeting in Chengdu, Sichuan, to integrate technological and industrial innovation and promote high-quality development.

• September 27 and August 23: Regular forums led by NDRC Director Zheng Shanjie to gather insights and discuss private sector challenges.

• June 5: A session in Shenzhen, Guangdong, on strengthening the private economy through long-term loans and tech financing.

• April 2 and May 6: Forums addressing equipment upgrades and recycling, driving industrial efficiency.

• March 22: A Wenzhou, Zhejiang, meeting celebrating private sector innovation and contributions to national development.

These dates highlight the NDRC’s proactive strategy to support private businesses in navigating external challenges and fostering high-quality, sustainable growth. This consistent engagement with the private sector underscores China’s cautious yet committed approach to strengthening its economy while balancing external and internal pressures.